While shrinking population increasingly affects more and more countries around the world, there is a significant geographical concentration in this respect. Most states that have already experienced considerable population decline are post-Soviet countries however, within this area, the population loss is also significant in Central and Eastern Europe (CEE). The total population in CEE which includes the 11 countries that joined the EU after 2000, decreased from 111 million to 102 million between 1990 and 2020. The unique aspect of this region is indicated by the fact that only 20 countries globally have faced a population decline between 1990 and 2020, and six of the top ten fastest shrinking populations belong to the CEE region. Another aspect that warrants further investigation is the heterogeneity of population change across regions. Despite similar historical backgrounds, significant variation in population change can be observed across countries during this period.

“A New Approach to Understanding Population Change in Central and Eastern Europe” in Population and Development Review presents a novel approach to decomposing population change and applies this scenario-based decomposition method to gain deeper insights into population dynamics in Central and Eastern Europe. This approach enables us to identify contributions of fertility, mortality, net migration, and initial age structure separately to population change. Its advantage lies in the additivity of the results: the impacts of the different factors along with the interaction effect sum up to the total change, transforming simple scenario analyses into a comprehensive decomposition. In addition, this method accounts for spillover effects, illuminating the long-term consequences of changing demographic factors (such as fertility or migration) on the size and composition of future generations.

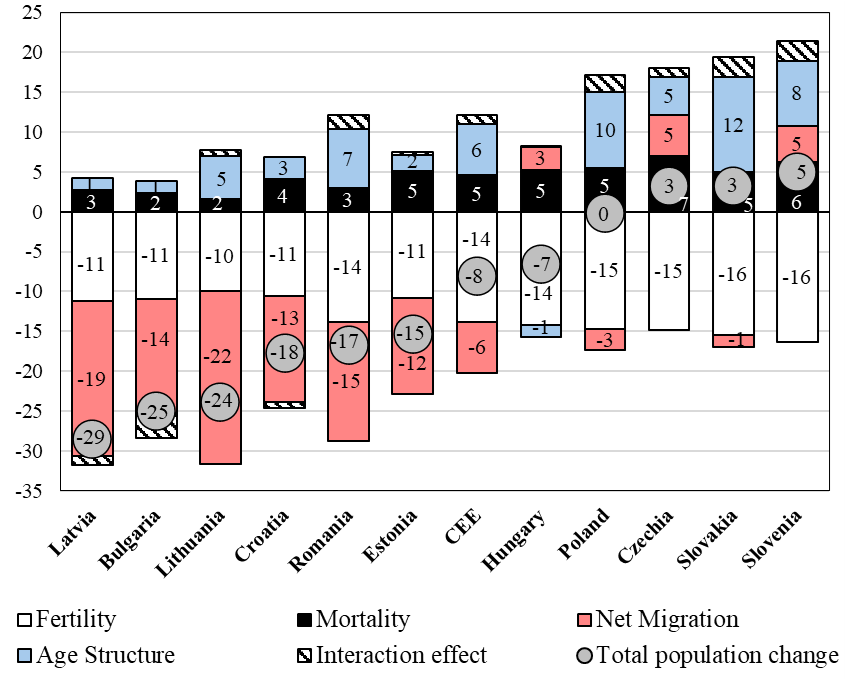

The population of Central and Eastern Europe declined by 8% between 1990 and 2020, with significant country-level variation ranging from -29% (Latvia) to +5% (Slovenia) relative to the initial 1990 population. We found that this population loss was driven by a 14% decline due to low fertility. It implies that, had fertility remained at replacement level throughout the period, the region’s population in 2020 would have been larger than the observed population by approximately one-seventh (15 million) of its initial size in 1990. In addition, the negative net migration reduced the population by 6% (7 million) by the end of the studied period. However, these effects were partially offset by a 5% (5 million) improvement in mortality and a 6% (7 million) contribution from initial age structure relative to the population in 1990. It demonstrates that the positive impact of the relatively young initial age structure in the CEE region was as large as the population-reducing effect of negative net migration. In addition, the positive impact of improved mortality could offset a one-third of the population-reducing effect of low fertility.

When examining the role of individual demographic factors in country-level population change, we find that the effects of fertility and mortality were relatively consistent across countries, as most exhibited similar patterns over the study period (1990–2020). The population-reducing effect of below-replacement fertility ranged from 10% to 16%, while the positive contribution of mortality improvements led to population increases of 2% to 7% of the initial population. In contrast, the impact of net migration varied substantially across the region, ranging from +5% to –22%, reflecting divergent country-level migration trends. The contribution of the initial age structure also differed significantly: in some countries, it increased the population by 10% or more, while in others, its effect was minimal or even negative.

Figure 1. Decomposition of population change from 1990 to 2020

(in percent of the population in 1990)

One of our key findings is that initial age structure played a crucial role in population change across the entire region. Without its contribution, not only the CEE region as a whole but also each of the 11 individual countries would have experienced population decline between 1990 and 2020. Using our new decomposition method, we demonstrated that the heterogeneity across the CEE region is more complex than previously assumed. While migration is an important factor explaining differences in population change, the initial age structure also plays a crucial role and must be considered for a comprehensive understanding.

Our findings offer valuable insights for public policy from multiple perspectives. Many countries concerned about actual or expected population decline focus their efforts on slowing down or even reversing this trend, primarily by implementing a wide range of pro-natalist measures to increase fertility. We emphasize that reducing mortality can also make a significant contribution to population growth or help mitigate decline. Therefore, investments in improving healthcare system efficiency and accessibility, promoting healthy lifestyles, and supporting mental and physical well-being not only benefit individuals but also help counterbalance population losses from other factors.

While our results highlight the importance of reducing mortality, they also underscore the limits of public policy. A population’s age structure is shaped by past fertility, mortality, and migration trends, and can be viewed as a form of demographic inheritance. Our novel decomposition approach demonstrates that this demographic inheritance has a powerful and lasting influence on population dynamics. In this sense, population change exhibits a form of path dependency—where past trends continue to shape future outcomes, regardless of present-day interventions.

Csaba G. Tóth, ELTE Centre for Economic and Regional Studies