Child marriage and early childbearing—marriages and births to girls below age 18—are serious threats to girls’ wellbeing everywhere. The mere existence of child marriage as an institution causes parents to invest less in their daughters’ futures, girls to drop out of education earlier, young girls to become mothers, and women to have less autonomy in all aspects of their lives. Adolescent fertility causes additional hardships, like keeping families in poverty and worsening the health of girls and their children.

Every year, some 10 to 12 million child marriages occur and 5.5 million girls below age 18 give birth globally. Often, child marriage itself is the main path to early childbearing, but it is not the only one. Girls may also get pregnant outside of marriage and some of them get married before the birth, some give birth as unmarried, and others terminate the pregnancy. The last large-scale analysis of the relationship between child marriage and adolescent fertility was conducted nearly twenty years ago using data from the 1990s and found that about 90% of adolescent births occurred to married girls in developing countries. How has this relationship changed since the 1990s? Is early childbearing still primarily taking place within child marriages? How does this relationship look in other parts of the world and for countries at different levels of development and at different levels of adolescent fertility? These are the questions we sought to answer in our new paper in Studies in Family Planning where we present an updated overview of the relationship between child marriage and adolescent fertility since 2010.

Our analysis captures the experiences of girls across as many countries as possible by using a wide variety of data sources. This includes well-known international surveys, like the Demographic and Health Surveys and Multiple Indicator Cluster surveys, country-specific surveys, vital registration statistics, and – in one case – data reported in an academic article. We also used newly published estimates of the number of births below age 18 in the 2022 revision of World Population Prospects to calculate global and regional estimates of the share of adolescent births by marital status. By using many different sources of data, our analysis describes the marital context of about 5.3 million—or about 95%—of the births to girls below age 18 that occur worldwide and covers 106 countries.

A major geographical shift in adolescent fertility has taken place over the past several decades. In 2000, about 40% of the global number of births to mothers below age 18 took place in Central and Southern Asia and 30% in sub-Saharan Africa. By 2020, the picture changed dramatically. More than half of these births took place in sub-Saharan Africa and just 16% in Central and Southern Asia.

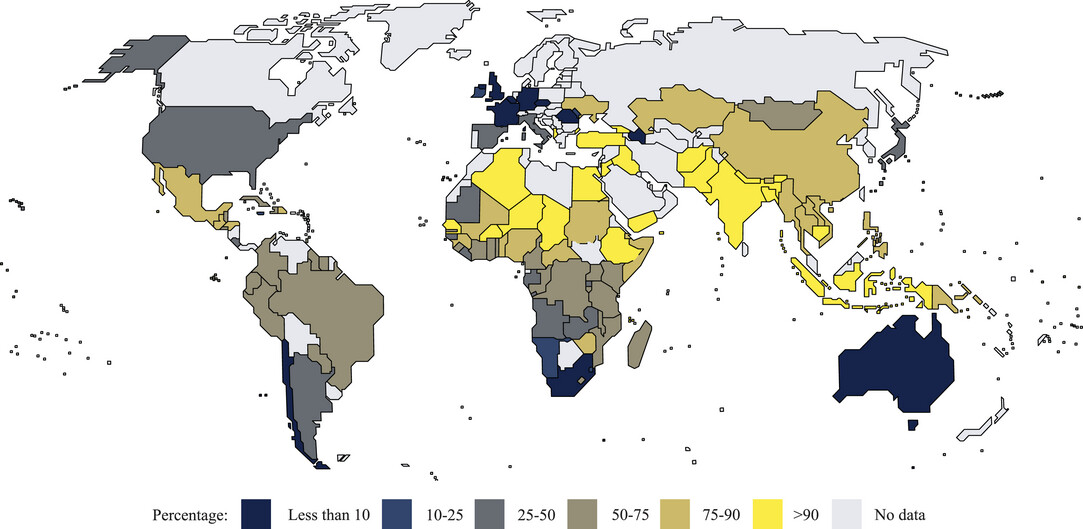

Globally, about 76% of first births to girls below age 18 today take place within marriage. There is a lot of variation across and within regions (see figure). Virtually all births among girls below age 18 are within marriage in Northern Africa, Western Asia, and South and Southeastern Asia. In other regions, particularly Europe and Northern America, where childbearing below age 18 is uncommon, few of these births occur within marriage (less than 30%).

Figure 1. Percentage of first births to girls below age 18 occurring within marriage/union, 2015.

For about half of the countries with available data, we can observe how this relationship is changing over time. What we find is that, in 40 of those countries, the share of adolescent births occurring within marriage has declined since 1995 to 2009. However, in many countries with the largest overall number of adolescent births, such as Bangladesh, Pakistan, Indonesia, and Nigeria, there has been little to no decline in the percentage occurring within marriage.

Based on current United Nations projections, by 2050 more than two-thirds of the global number of adolescent births will occur in sub-Saharan Africa, and we can therefore expect that the relationship between child marriage and early childbearing at the global level will increasingly resemble the patterns found in that region – where child marriage drives much of adolescent fertility, yet a substantial share occurs outside of marriage. If we are to eliminate child marriage and reduce adolescent fertility, the full set of the upstream factors that cause them must be addressed: lack of economic and education opportunities for women, overall economic hardship, lack of information about and access to contraception, and strong social norms supporting the practice of child marriage.